I have a very small audience. You can look up my follower counts on LinkedIn and Twitter to get a sense, but needless to say, I’m not exactly ready to launch my burger chain yet. You gotta start somewhere....

One thing that I’ve been more conscious of since starting my newsletter is that, even among my small following, it’s really hard to understand anything about who is seeing or engaging with my posts, tweets, etc. Part of this, as I keep writing, is due to platforms mediating my relationship with my audience. Here’s what Twitter shows me about what happened with my tweets in September:

If I click on ‘View Tweet activity’ I can see more data on categories of activity (e.g. Detail Expands and Link Clicks), but nothing about who was actually doing it.

From a user privacy perspective, this makes some sense. In an increasingly algorithmic online world, I don’t think I have the right to know who happened to scroll by my tweets. But what bothers me is how hard it is to tell who publicly engaged with me. These are people who raised their hands (or at least moved their thumbs with slightly more vigor) to tell me that they liked (or took issue with) something I had to say in a way that they knew would be publicly viewable by everyone. Ten people mentioned me last month, 9 people followed me, and a whole bunch more liked and retweeted my posts. But to find out any specifics about these people—who, again, posted publicly—I have to either manually read through all my notifications or turn to Twitter’s data API. For a company that makes writers, creators, and community a core part of its pitch, Twitter is remarkably blase about the tools it directly affords.

LinkedIn provides some demographic information on people who engage (unsurprising revelation: the top two job titles of people who engage with me are ‘co-founder’ and ‘product manager’) but is otherwise similarly sparse.

I know from Substack that LinkedIn is the strongest referral source to my newsletter, but I have no way of telling, on LinkedIn’s site, which of my posts were better or worse at driving traffic without paying to access LinkedIn’s Share and Social Stream API. To me, this is even weirder than the lack of accessible audience data on Twitter. LinkedIn is all about professional connections, but here are these PROFESSIONALS who are CONNECTING WITH ME about my work, and LinkedIn doesn’t give me any organized way to understand who they are or how we might benefit from interacting further.

There are a few services out there that could help me understand my followers better. Hubspot, Hootsuite, and Zoho all offer various tools to let me see who’s engaging with me in one place. However, If data access is one problem when it comes to what creators know about their audience, I think a much bigger one is data usefulness. Substack, for example, gives me complete transparency on my email list. Unlike on the big social platforms, I can get in touch with people who subscribe to my newsletter whenever I want to. But having a list of email addresses doesn’t help me accomplish any of my goals by itself. Instead, I need something outcome-driven to:

Grow my audience

Make better content

Make more (good) content

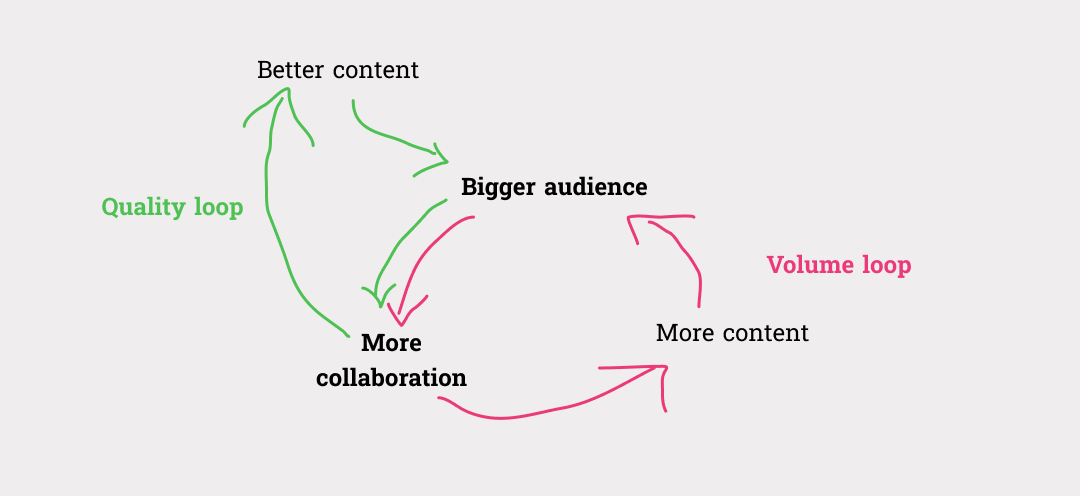

Or maybe all three. I believe there are a few (potentially) virtuous cycles at play around how creators leverage their connection with their audience:

The first cycle, in blue, is around leveraging feedback. A bigger audience means more people actively engaging with your work. In particular, that means more people who will tell you what they liked about it—and what they didn’t. All that feedback has the potential to help a creator produce stronger work. One thing I want to investigate in more detail in a future post is the growing trend of creators editing their work after it’s live, for reasons ranging from legacy, to maintaining lore consistency, to managing copyright disputes, to editing out lyrics that listeners found objectionable. But it’s this last one, editing based on user feedback, that I want to focus on today.

Creators today have an unprecedented ability to act on feedback from their audience, both because it’s easier to aggregate that feedback and because, by producing digital work, it’s possible to change the work that’s out there in a much more impactful way than if a million hard copy DVDs were already circulating. No, you can’t edit your YouTube video after it goes viral (though now you can edit your tweets!), and there are real questions of journalist integrity involved in editing work without disclosure. But at a minimum, you can edit your distribution strategy to emphasize the parts of your long-form content that are most successful.

Gary Vaynerchuk has a great post about his highly successful content strategy, where he breaks down how he takes a piece of ‘pillar content’ and then iteratively publishes it across multiple platforms and formats, adjusting based on the implicit and explicit feedback of his audience. But this strategy is out of reach for most creators. As a publisher friend said to me recently, “we have data across all these platforms. But we don’t know what decisions to make based on it.” I think there’s a lot to be built to help creators make and, crucially, execute decisions based on audience input, rather than just aggregating and presenting it.

Beyond the post-facto feedback cycle, I there’s more that creators can do to learn from their audience during the creative process. This is where the quality and volume loop comes in:

A bigger audience doesn’t just lead to more feedback on existing content, it also has the potential to enable more collaboration around stuff that’s not yet published. Until fairly recently, I was a paid subscriber to Matt Taibbi’s newsletter, TK News. Taibbi sometimes repurposed content that he had originally used elsewhere and it was particularly interesting to contrast those highly edited posts with his looser takes. I had the feeling, as I read his work over time, that I was watching him turn over some of the same ideas, strengthening his arguments—and writing—along the way.

I think this is a really interesting use of the newsletter format. As I’ve written in the past, the solo-operator newsletter format works best for personal takes and is much weaker for investigative journalism, beat reporting, opinion writing—basically any format that benefits from strong feedback and, perhaps more importantly, pushback on the ideas being presented.

But what if your audience could provide some of that guidance? And what if they had an incentive—beyond the joy of interacting with their favorite creators—to help make your content better? I never emailed Matt Taibbi, but certainly some subscribers did and some subset of those email responders must have had useful feedback. Taibbi, who has access to professional editors when he wants them, probably isn’t willing to pay (or discount) readers who give him good feedback. But for the vast majority of creators who can’t pay an editor, I wonder if having a sort of rough-draft community of readers might be able to fill the gap.

Casey Newton touches on this potential in his rundown of what he’s learned in his first two years writing on Substack:

Sidechannel [Newton’s discord channel] never quite lived up to the expectations I had for it as a kind of collaborative newsroom of independent journalists. But a solid group of you show up there every day to drop links, share commentary, and analyze events with me in real time. It has been an incredible resource for me this year, in sometimes unexpected ways — such as when some lawyers who had previously argued in Delaware Chancery Court helped us pick apart Elon Musk’s Twitter lawsuit.

Sidechannel, as Newton describes it in his launch post, was a place for collaboration among independent professionals with shared goals. While I’m not convinced that every writer or creator needs their own Discord server or Slack instance, I agree with Newton when he says that he (and, I think, creators in general) have “realized only about 1% of the value of having a Discord server.”

So what’s in the 99%? As with the feedback loop, I believe that true value lies in driving outcomes, rather than in simply enabling discussion. I think there’s both an incentive problem and a technology problem: how do you get people to feel like working together is mutually beneficial, even when one of them (the creator) is running the show?. As great as Discord and Slack are at enabling rapid, simultaneous communication across topics,* it’s a lot less great at making things happen. And for a busy writer or creator trying to build the next Morning Brew, more (and better) content that resonates with your audience is the only thing that matters.

*Whewph, a lot to discuss on this topic too. I ❤️ Slack and Discord...but also.

As always, thanks for reading! Please send me a note if you have feedback or want to discuss. And why not give this post a share?