Social media is broken for creators. Blockchain can help.

At least the principles of blockchain can. And maybe eventually the technology itself.

Like many people, I’ve been disturbed by the rapid rise in censorious action from the big tech companies that increasingly control our access to the internet. As I mentioned in my first post, when I joined Twitter in 2015, executives running orientation sessions were still describing free speech as a core company principle. As late as 2019, Mark Zuckerberg was arguing that “we need to recognize what’s at stake and come together to stand for voice and free expression.”

But a lot has changed since then. Today, both Facebook (where I also worked) and Twitter have shifted their focus toward preventing harm—from violent content, spam, and what they deem to be untrue or misleading information, among other things—often at the expense of free expression. Even if you believe, as I do, that it’s a worthy goal to pursue both objectives simultaneously, it’s hard not to get whiplash from the massive shift in both companies’ values.

As a user, you have virtually no direct say in what you see on social media. Yes, you can control who you follow, though this is rarely a strict filter: see, for example, the rapid rise in Shirts That Go Hard on Twitter. What you engage with and where you linger also implicitly impact the content ranking algorithm. But in practice, you have little explicit control over what you see. And if a platform decides they don’t want you to see something (say, an unflattering article about a presidential candidate’s family), then they have absolute authority to prevent you from seeing it.

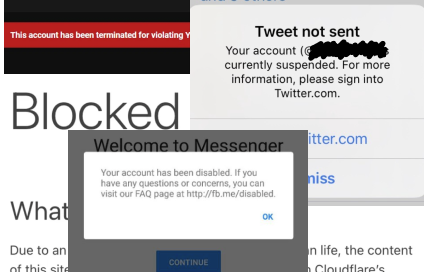

The situation is even more tenuous from a creator’s perspective: say something that YouTube doesn’t like once and they’ll suspend you. Keep saying it and you might permanently lose access to the platform(s) where you make your living.

There’s a persistent argument that creators—writers, journalists, vloggers, artists and more—should just go elsewhere if they don’t like the rules on any given platform. I touched on this in my post a few weeks ago. But this argument belies three crucial counterpoints. First, in spite of creators’ formal copyright to media they share on most platforms, they don’t actually have guaranteed access to it. Most people do not make a habit of backing up tweets or Facebook posts. In fact, a lot of people I know use YouTube as a backup for their videos. If YouTube decides to lock you out of your account, those videos get locked up along with it. Depending on where you live, you may be able to request a download of all the data (including media) that a company has on you. But even if you had it, what then?

This is the second counterpoint: even if a creator has access to her content, she do not control her relationship with her audience. How is a user, locked out of her Twitter account, going to get in touch with the people who loved her tweets once she stands up her...independent website? Some new platforms, like Substack, have tried to address this issue by giving creators the email addresses (with permission) of their readers. In theory, policies that give creators direct contact information help those creators maintain connection with their audience.

But (point 3) don’t get too excited because, as I mentioned last time: a small number of people make the decisions about what we can say online, and these people change their minds a lot. Cloudflare’s recent kerfuffle over whether to ban Kiwi Farms is a case in point. Taylor Stuckey wrote an excellent explainer of the whole thing that you should go read. The basic summary is that Cloudflare, a company that provides security and hosting products to websites, was facing a mounting social media campaign to deny service to Kiwi Farms, a fringe forum where users often make cruel and disturbing posts about other people, over posts about a Twitch streamer and activist who goes by the name Keffals. Over the course of 3 days, Cloudflare first defended its hands-off approach (without naming Kiwi Farms) and then caved to intense online pressure by blocking users from accessing Kiwi Farms while simultaneously claiming that doing so was ‘a dangerous [decision] that we are not comfortable with’.

All of this is to say that companies are not democracies! Of course they are bound by the laws of the countries in which they operate, but beyond that, they are dictatorships of their leadership, board, and, increasingly, activist investors. I believe Substack, Netflix, and the growing video platform, Rumble, when they defend free expression on their platforms. Heck, I believed Cloudflare for a few days too. I think the principle they spelled out in their first blog post, namely, that an internet company’s accountability for content on its platform should increase the closer it gets to being a publisher (and decrease the closer it gets to being core web infrastructure) makes sense. But recently history demonstrates that trust alone is not enough. Societal, government and employee pressures evolve over time. No matter where you fall on any of the debates above, it’s an undeniable issue for the internet that nothing structural prevents tech companies from dramatically reversing their policies at any point.

This is where blockchain technology comes in. For creators of all sorts, blockchain has the potential to guard against deplatforming and ensure durable access to their media and audience.

When most people think of blockchain, they think of cryptocurrencies, such as Bitcoin or Ethereum. And it’s true that the most obvious use of blockchain technology for writers and creators is in protecting their financial interests. Once a writer and a reader have agreed to payment terms using a blockchain-based system, no one—including the platform—can change the rules.

This structure offers an important check on the decision-making power of the platforms. Even if you do not believe, for example, that the organizers of Canada’s Freedom Convoy were entitled to the $8M that they raised on crowdsourcing platform GoFundMe in February 2022, everyone should be concerned about GoFundMe’s novel assertion (since-abandoned) that all that money would instead be donated to a charity that they approved. Under a blockchain-based system, GoFundMe could have refunded donations, as they ultimately chose to do. However, their assertion that they could do something else with the money would not have been possible—unless everyone had agreed to give them that power ahead of time. The donor, receiver and, I would argue, the platform are all better off when they are tightly bound to honor a mutual commitment.

Beyond payment assurance, blockchain technology can also help creators retain access to their work and audience. A social media platform built on blockchain could still choose to prevent people from seeing certain content in its app (or on its own website), but it could not stop people from either downloading that content directly from the blockchain or building an app with a different set of rules to surface it.

This is a primary sell of nascent blockchain based social protocols, such as Farcaster and Bluesky and publishing platforms like Paragraph and Sigle. From a user’s or creator’s perspective, this structure allows a much greater degree of data portability, something that is increasingly required by government data and privacy regulation. But in contrast to today’s regulations, which generally require data to be downloadable, data written to a blockchain would be usable. If a creator was censored based on platform A’s speech policies, they could easily port their old content to platform B.

Blockchain is not without challenges. The transparency and immutability that make blockchain so appealing for resisting censorship also make it harder to police illegal and undesirable content. Audius, a blockchain music streaming site has seen this challenge first hand, as copyright-infringing media has proliferated with little recourse for creators or Audius itself. Although there are startups working on this problem, it is not yet solved. And even though blockchain technology offers an answer to platform-level censorship, it cannot solve the larger questions of government-led censorship, nor even the DDoS attacks that Cloudflare was protecting Kiwi Farms from in the first place. If a sufficiently technically-savvy government or group of people wants some piece of content removed from a blockchain, they will be able to find ways to either force or badger its operators to comply.

So why would a company want to allow the transparency—of content, usage, and possibly engagement—that is a required feature of blockchain storage and payments?

The key reason is that it allows companies to get out of the hockey puck business of arbitrating truth. Using blockchain does not abrogate any company’s responsibility to suppress illegal content. And we all have a vested interest in not being harassed and bombarded with spam online. But reasonable people can disagree about what constitutes bullying and misinformation. Using a blockchain-based system would allow companies to continue to make and enforce their own policies, while also creating a meaningful release valve for people with different standards. This shift in user controls could help to rebuild the trust with users who believe that the largest platforms are making the wrong content moderation decisions on their behalf.

There are a variety of startups building blockchain-based media publishing platforms (Audius for music, Mirror and Sigle for writing, Mastadon, Orbis and Steemit for more realtime communication, to name a few). However, perhaps tellingly, none of them makes censorship resistance its sole pitch. For most platforms, speech policies only start to matter at scale: when your community is small enough, trust is higher and the gray areas around content are smaller. These new platforms need to provide additional value—whether its news methods for defining ownership of your work, new ways to connect with audiences, access to new funding mechanisms, or something else—to both pull people away from incumbent players and get users and creators over the considerable blockchain onboarding hump. So far, no company has done so at scale.

On the flip side, among incumbent platforms like Twitter, the problem is in some ways reversed. Beyond the significant technical hurdles, these players have much more to lose from introducing transparency. While Twitter has funded Bluesky and many media companies have gotten into the NFT game, no incumbent content platform has taken a big swing at rebuilding on blockchain.

But the problems of moderating an increasingly complex user and media landscape are not going away. And it only takes one scandal or one superior mechanic to pull people from wherever they’re currently creating or consuming. Blockchain offers one way to move forward, but it is not the only one. As platforms proliferate to offer both greater control to content creators and publishers the principles that led to the development of blockchain technologies can also help. Like the CEO of Cloudflare, I believe that a large part of the problem with the current state of content moderation lies in transparency and accountability. The more that platforms…

1) Articulate their principles (like Cloudflare)

2) Apply their principles consistently (like no one)

3) Provide the reasoning for their decisions (like a pending Florida law is trying to force social media companies to do)

4) Empower independent bodies to make moderation decisions (like Facebook has tried and, so far, failed to do)

…the more they can rebuild trust in the tenuous relationships they have with users, creators and even governments. These are the tenets that a blockchain-backed system would enforce. But you don’t need to change your stack in order to change your attitude.

As always, thanks for reading! Please send me a note if you have feedback or want to discuss. And why not give this post a share?